So, uh, what is CES anyway?

I'll admit it - it took me a long time to understand what cauda equina syndrome actually is.

In researching our CES book, I learned that this is not unusual! I spoke to a lot of clinicians about CES, and a lot of them admitted they didn't really get it. They knew the 'CES red flags', and they knew CES had something to do with disc herniations and nerve roots... but beyond that, the details got a bit hazy!

If that sounds familiar to you, then this blog post should be useful. I'm going to point out a few things that might help you to flesh out your understanding of CES.

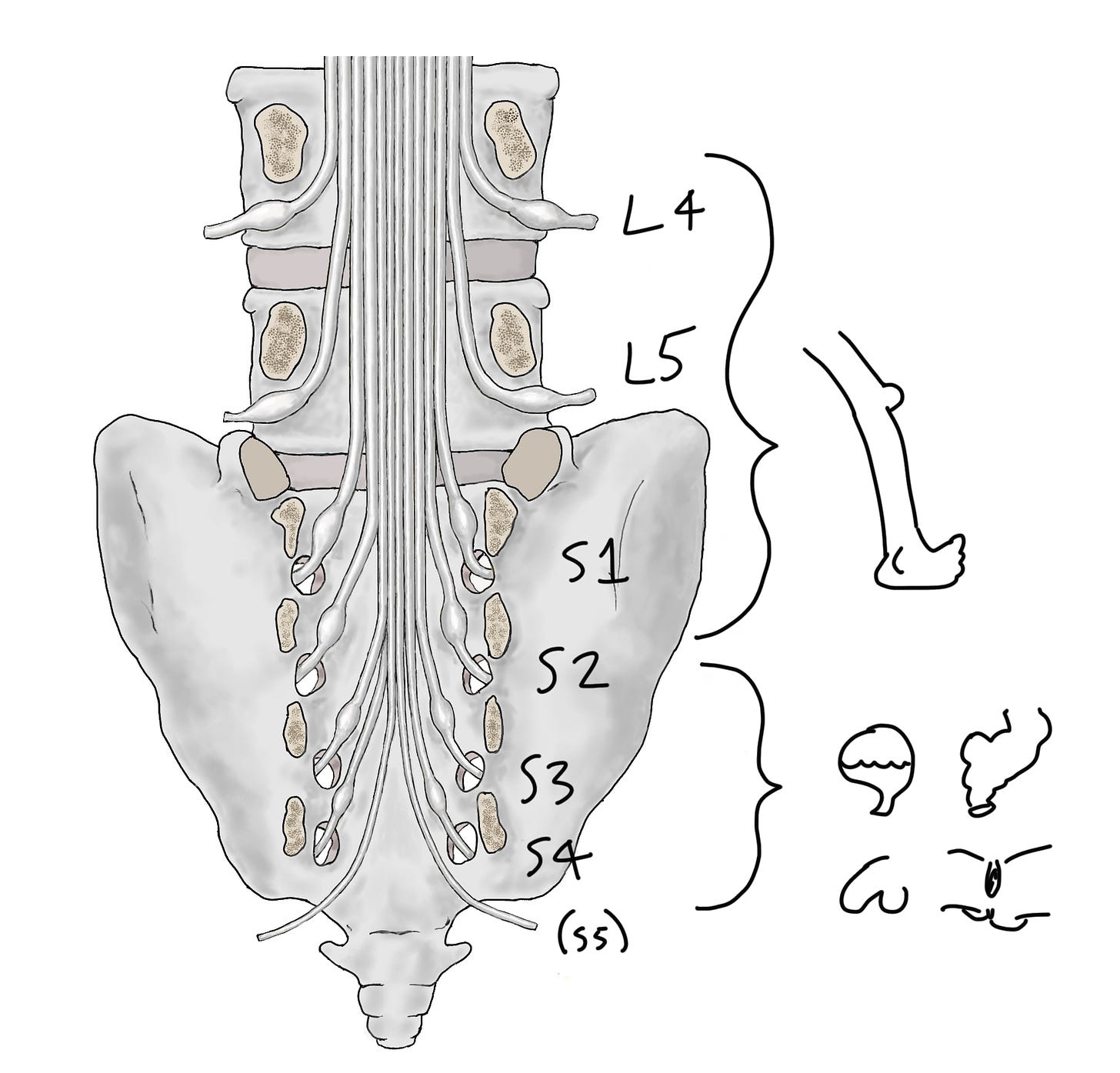

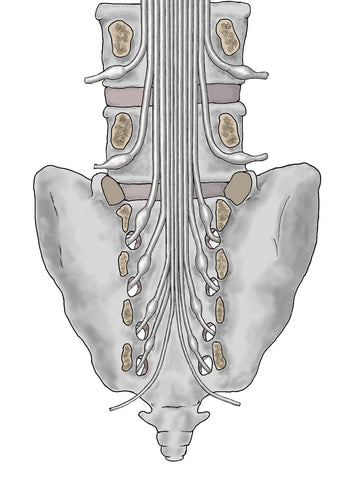

Let's start with this picture (from our book!) of the lumbar and sacral nerve roots. Remember the nerve roots basically link the central nervous system to the peripheral nervous system. This whole hanging bunch of nerves is the cauda equina.

Now let's split the nerves into two groups.

-

L4, L5 and S1 are all going to go into the lower limbs. When you do a neuro exam, testing strength, sensation and reflexes in the legs you're partly testing the function of these roots.

-

On the other hand, S2, S3, S4 and S5 are all going (mostly) to go into the pelvis. When you ask your red flag questions about bladder and bowel function, sexual function and saddle sensation, you're asking about the function of these nerve roots. It's when these roots are injured that bladder, bowel, sexual and saddle function are all impaired, and we call this cauda equina syndrome.

How are these nerve roots injured? Mostly by things that press on the cauda equina. For example, vertebral collapse and vertebral slippage, stenotic overgrowth, tumours, aneurisms... But the most common cause is a disc herniation.

However, it has to be a particular, rare kind of disc herniation.

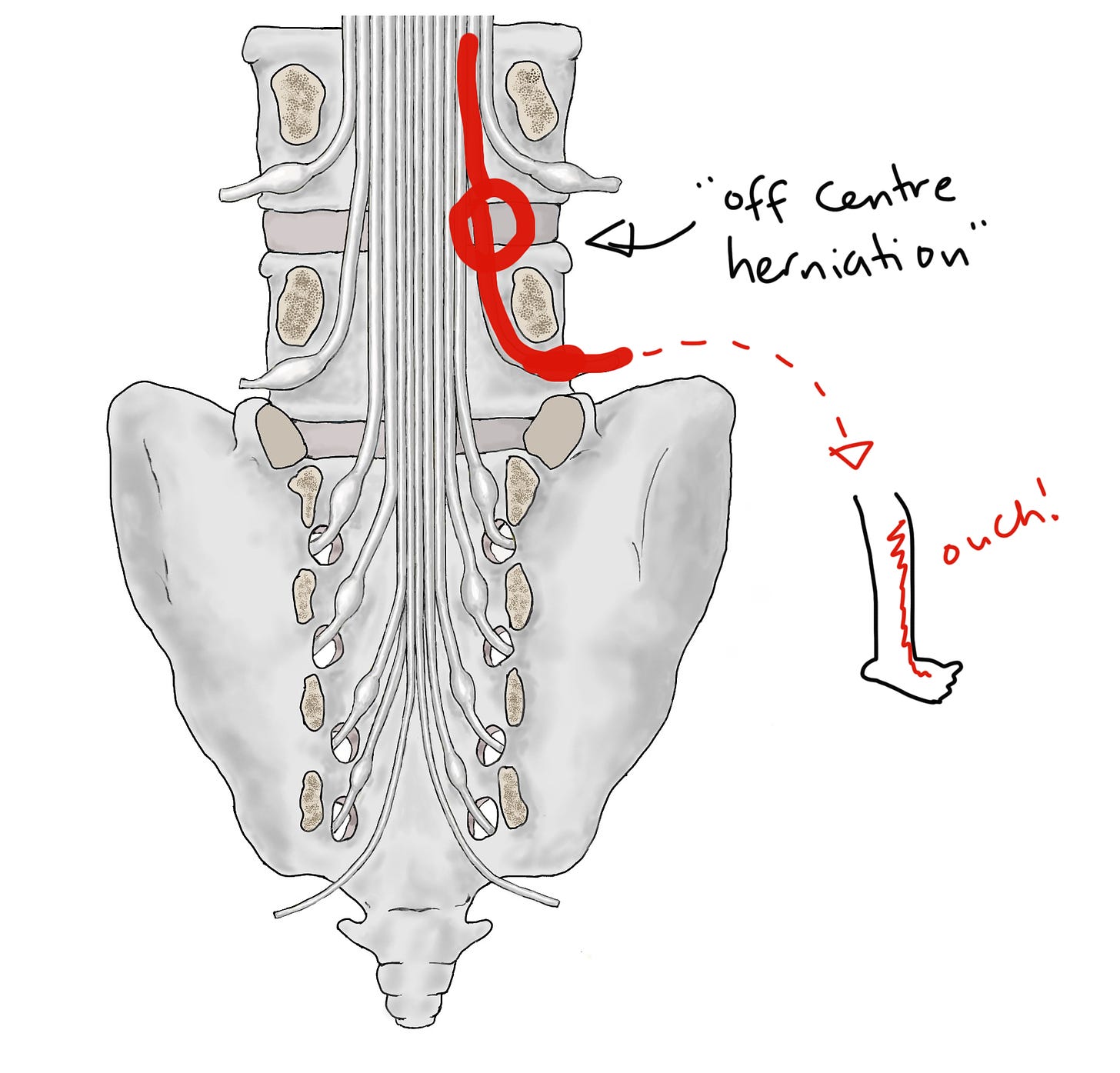

The most common kind of disc herniation, which does not cause CES, is an off-centre herniation, at this point:

As you can see, this kind of herniation injures one single nerve root as it's veering off from the rest of the cauda equina. In this case, the right sided L5 nerve root. This doesn't cause CES, because S2-5 are unaffected. Instead, it causes sciatica (more properly called radicular pain or radiculopathy). Sciatica is really common, as we know.

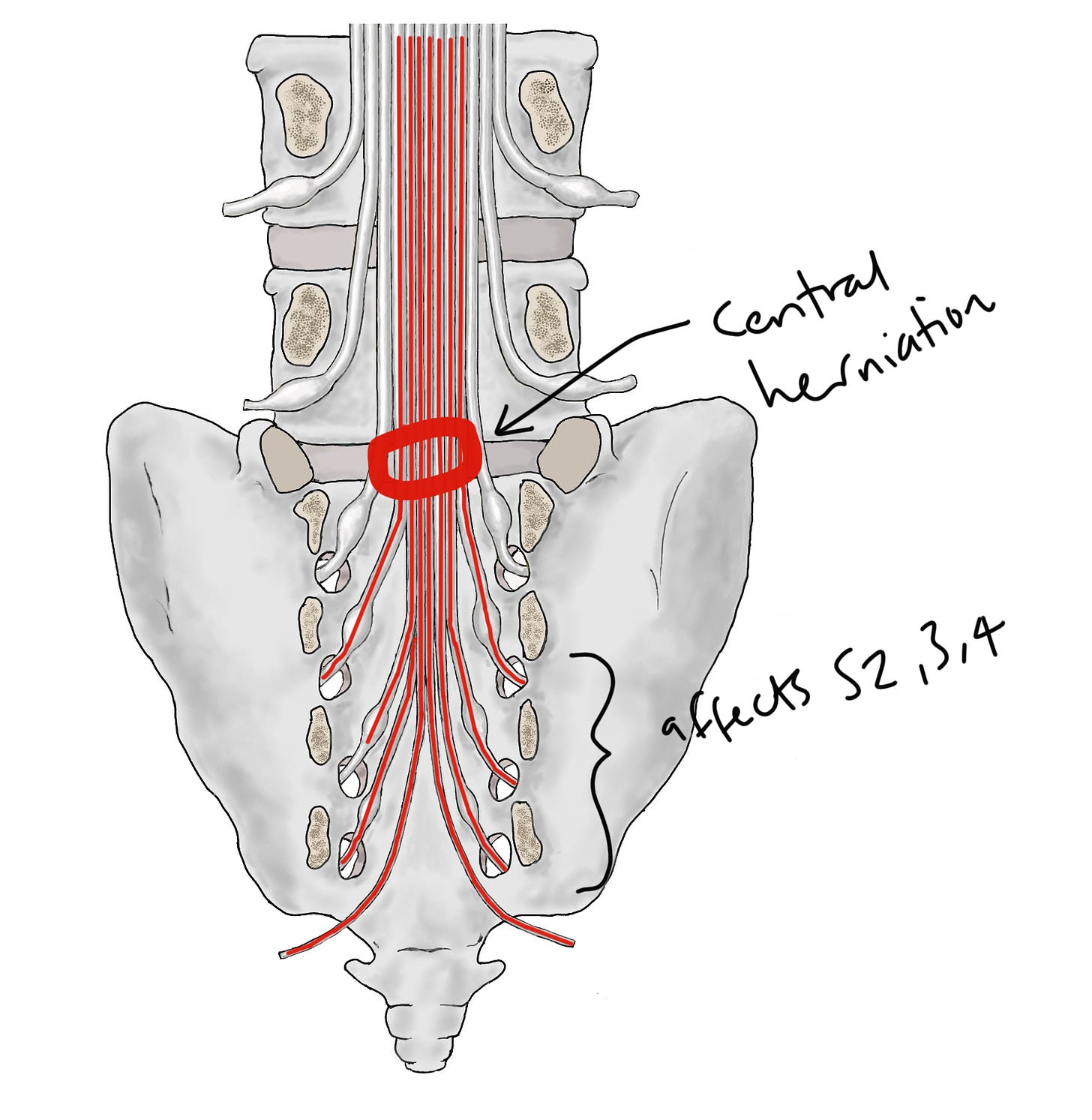

At the risk of stating the obvious, this kind of common off-centre herniation can't injure S2-5 because... there's no discs in the sacrum, where those nerves veer off! Instead, the kind of disc herniation that injures S2-5, which does cause CES, is the more rare central herniation, at this point:

It might seem like a small difference in location, but you can see how it has a big effect because now S2, 3, 4 and 5 are in the 'firing line'.

So this clears up a common point of confusion, which is that lumbar disc herniations cause sacral nerve root injuries, and therefore CES. It's because they injure sacral nerve roots as they're passing through, on their way to the exit points in the sacrum.

It might be worth looking at a picture of all that anatomy in 'real life'; thanks for Jose Paulo Andrade for the photo:

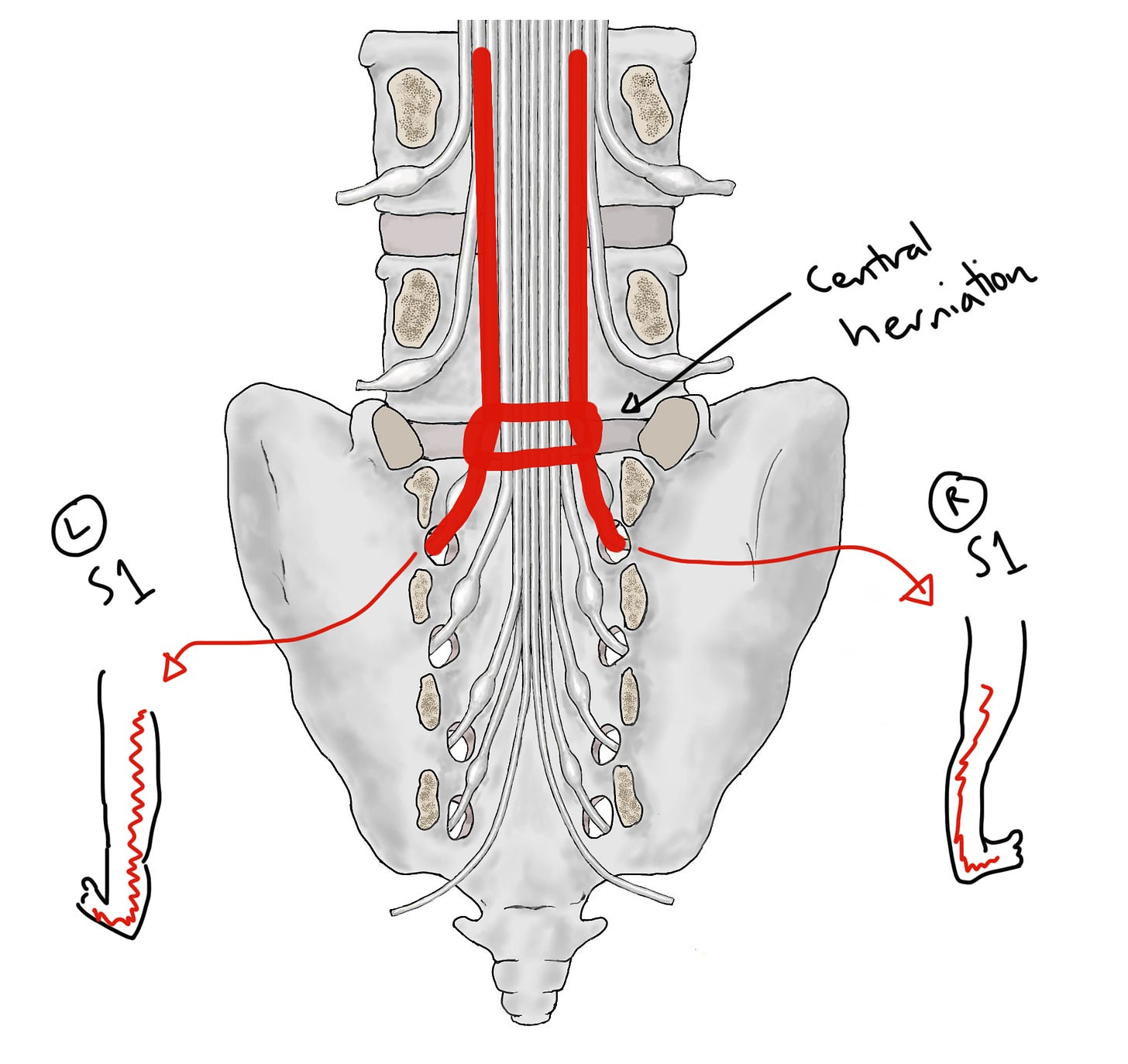

Next, let's look at why 'bilateral sciatica' is a red flag for CES.

If we go back to our picture of a central disc herniation, you can see how the herniation can ‘catch’ both of the nerve roots that are going into the leg, too (in this case, the S1 roots), and cause bilateral sciatica.

So the chain of thought behind bilateral sciatica being a red flag is: 'This person has bilateral sciatica!' —> 'Something might be pressing on both their left and right sided nerve roots!' —> 'That probably means a large central mass, which is probably also pressing on their S2, 3, 4 and 5 roots!' —> 'Maybe they have CES!!'

(It's worth saying though, that actually about half of people with CES have unilateral sciatica... So bilateral sciatica is not necessary for CES... it's just a major warning sign).

Finally, I another useful thing to know to understand CES is that it's a condition that unfolds over time. Although the red flag questions can make CES seem like a static thing, in fact the symptoms can unfold over hours, days or weeks, starting with very subtle signs and progressing to very serious ones.

Take, for example, bladder dysfunction. Most people know that urinary incontinence is a symptom of CES. But earlier symptoms might be less obvious changes to Frequency, Flow or Sensation (to remember think F.F.S.!)

For example, someone with CES might urinate more often than normal, because their bladder isn’t emptying properly (a change in Frequency). Or they might have to strain to start urinating, or find that when it comes out it’s just a sputter or a dribble (a change to Flow). Or they might not be able to feel it properly when they’re urinating, perhaps so that they only know they're going because they can see it or hear it hitting the water in the toilet bowl (a change in Sensation).

These are all symptoms of an incomplete injury to the S2, 3 and 4 nerve roots... they've not stopped working, but they are working less well.

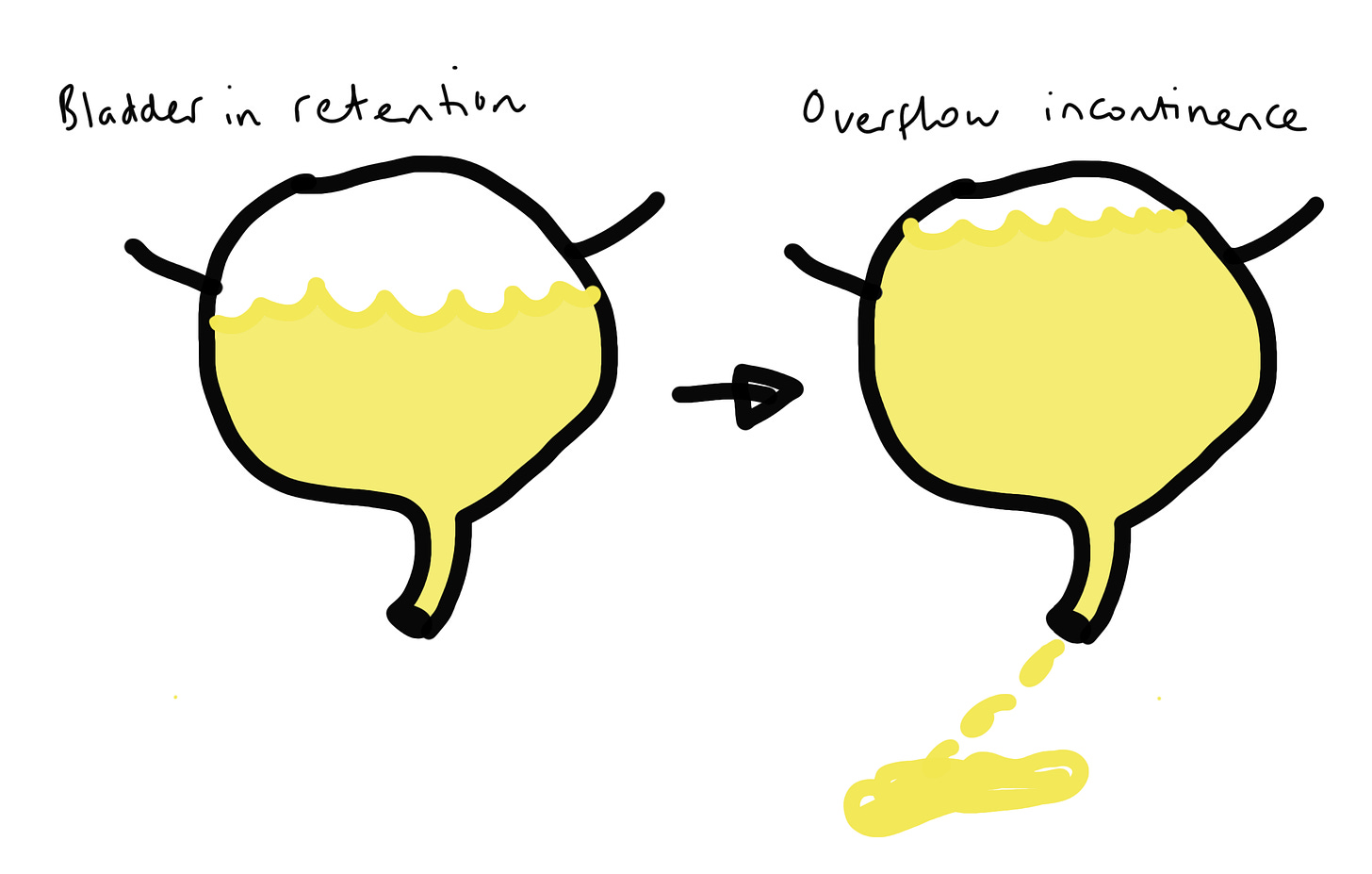

The incontinence we tend to associate with CES is actually the end-stage of bladder dysfunction, when S2, 3 and 4 are barely working or not working at all. The bladder becomes paralysed and insensate and urine builds up inside. Once it builds up enough, there's no more room in the bladder so it leaks out: overflow incontinence.

I think that's a good place to leave it... Hopefully this helped you to begin to understand CES a bit better!

There is, of course, much more to say, which we cover in our book, Cauda Equina Syndrome: The Clinician's Guide.